Photo by Selena N. B. H. via Flickr

A number of coaches advocate using a small subset of drills and practice plans throughout a season to train their players. I don’t think this is the best way develop high quality players and here’s how I came to that conclusion.

The advocates of the small subset correctly point out that once the players get familiar with the drills that they are going to be using throughout the year, their practices run very smoothly and efficiently. Some coaches have even proudly boasted that their players are so familiar with their practices, they could sit on the bench with hardly a word or two and run their practice.

So why do I think that the small subset concept is a bad idea?

First, hockey is an open sport, meaning that there is a large random component to the play (i.e., you can’t reliably predict what is going to happen next). For the most part, the challenges and decisions that a player faces are unique and unscripted (unlike closed sports like gymnastics and figure skating). Practicing the same thing over and over again is training for a closed sport. While the player gets very good at executing the physical skills necessary to perform the drill, the real important skills like decision making / reading and reacting are not taught. Rote repetition does not a smart hockey player make.

Second, placing someone in an enriched environment where they are able to explore and experiment in many unique and stimulating situations actually affects brain development particularly in younger players (please see “Brain Plasticity and Behaviour in the Developing Brain”). Experience in challenging and exciting environments actually builds the physical capacity of our brains.

Third, let’s face it, doing the same drills over and over again is boring. I hear many coaches who complain of mid-season slumps and a lack of motivation and energy half-way through the season. Very often it’s seen as coaches “losing the room”. What’s often happening is that they have a very bored group of players wanting to push their limits but are being stifled and limited instead. If you have exciting and interesting practices, which move players out of their comfort zone, you will have engaged and energized players from the first skate in pre-season to the final skate in the playoffs.

Finally, as coaches, our goal I believe, is to produce the highest level of performance from our players in competition, not practice. Practice is supposed to be ugly, filled with mistakes, and hard work for everyone involved, including the coaches. I can’t stress enough to my players that practice is, and should be, harder than any game they will ever play. If we are aiming to have players learn what we are teaching them, the evidence is stacked against those who want to use the same small subset of drills.

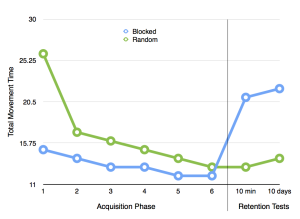

A neat little study was performed by Shea & Morgan where they taught study participants three different types of novel movements and recorded their time to complete the movements correctly. The lower their times, the better their performance. The researchers changed how the movements were practiced. Half the participants used a blocked practice structure where they trained movement A first, then movement B, and finally movement C (e.g., A A A A B B B B C C C C). The other half of the participants practiced using a random practice structure. Movements A, B, & C were practiced in a completely random order (e.g., C B B A B C A B C A C A).

When tested on their performance during the practice (called the acquisition phase), the group who practiced using the blocked practice structure outperformed those who practiced using the random structure for the first few measurements but by the end of practice sessions there was only a small difference. The interesting finding though was when they tested the participants after some time had passed (10 minutes after practice and 10 days after practice, called the retention test). In both situations, when presented with a random order of movements to be performed, those who practiced using the random practice structure outperformed those who practiced using the blocked practice structure; by a large margin.

When tested on their performance during the practice (called the acquisition phase), the group who practiced using the blocked practice structure outperformed those who practiced using the random structure for the first few measurements but by the end of practice sessions there was only a small difference. The interesting finding though was when they tested the participants after some time had passed (10 minutes after practice and 10 days after practice, called the retention test). In both situations, when presented with a random order of movements to be performed, those who practiced using the random practice structure outperformed those who practiced using the blocked practice structure; by a large margin.

So what does this mean for hockey practice? If we consider our practices the acquisition phase (where the players are learning), and our games the retention test (where we test what the players have learned) and we want our performances in games to be the best possible, then we should be using a random structure to our practice (e.g., lots of different types and variations of drills) rather than a blocked practice structure (e.g., the same drills over and over again). Of course, if we want our practices to look pretty, then by all means use the same few drills every time. You can even take a break and have a seat on the bench and let the players run through the drills on their own.

Give me your thoughts. How do you structure your practices over a season?

Cheers;

John

I agree and understand the reasons of having a diversity of drills… but what is the best way to optimize a practice ?!

I have 50 minutes a week (half ice) for my team to practice. If we remove the first 8 min for activation and the last 5 for power skating or intense skating, I have 35-40 minutes remaining to work on technical skills and system play (tactics).

If I lose time to explain 1 new drills 2-3 times it becomes critical cause I won’t have enough time to be as per my season plan. Itworst if the same situation applies for 2-3 new drills in the same practice.

I usually have a set of 20 drill (more/less) to select for our practices to avoid explaining too much to avoid waste of time.

I’m also limited in terms of drill knowledge… I don’t have a huge repertoire.

What would you guys do if you were in my situation to maximize my time and still develop the players ?! Any ideas ?!

Hi Sebastien,

Having limited ice time is a real challenge. Here are a couple ideas that you can try.

1) Have your players arrive early for practice and run through the drills with them before you step on the ice. I would recommend actually finding some space and physically doing the drills off ice. Easy to substitute a soccer ball, football, or rugby ball for the stick and puck. Added benefit is that the kids really enjoy this.

2) Prepare your practice plan several days in advance and provide a detailed description of each drill with your key teaching points. Send that out via email to each family and have them review it with their child. If the player is old enough you can send it directly to them.

While you will always have to eat away at some of your practice time with explanations, the players will benefit from the varied drills. Quality learning over quantity repetition.

-John